Your latest film, My Sunny Maad, was awarded the prestigious Jury Prize at the largest animated film festival in Annecy, France, in June. Why do you think the film withstood such a big competition?

I think the main credit is the model, screenplay, animation, art, direction, cast, music, sound, editing, producers, production, post-production, just about everything. And also some lucky star (laughter). In animated films, the characters and the plot are often simplified, which we did in part as well, but at the same time we tried to maintain the multi-layered nature of the story and the plasticity of the characters. One of the members of the jury wrote me that our film is touching, fragile. He appreciated the depiction of the characters, which is not simplified, each has several layers, they are complex, especially Nadir, which jumps from progression to traditionalism. For example, the journalists positively mentioned the emotionality

, the story and the acting of the characters. This made me especially pleased, because I was often very critical and bothered the animators, I returned the footage a lot for corrections. But the detailed work must have paid off for us.

What intrigued you about the novel Freshta by the writer Petra Procházková, that you chose it with the producers for a feature and, moreover, animated adaptation?

From the first moment, the book captivated me with its liveliness, its immediacy with which it describes life in an Afghan family. Until then, I was not particularly interested in life in Afghanistan, but thanks to the humor of the main character Herra, her slightly ironic comments from a European perspective, I found myself in a place I would never have been able to look at, the intimacy of a Muslim family. Suddenly you find out that, despite the many differences that exist there, there are many things similar, familiar to us. I was deliberately looking for a model that was not created for animation, I wanted to prove that even in animation it is possible to tell a multi-layered story as in a feature film. I chose the form of animation because it is my most natural expression. After all, there are already many animated films depicting real stories.

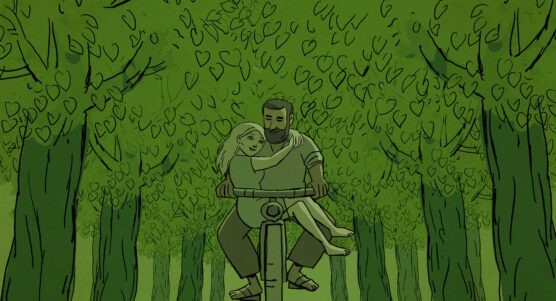

Herra leaves her native Prague to marry the Nadir from Afghanistan. What impresses her about Nadir as opposed to European men? Can you imagine leaving your country for your love to a country torn apart by endless war and, moreover, to such a different culture?

It may be just my personal interpretation, but I fully understood Herra. She felt she had met the man of her life, a real man with a capital M. A big bear with a tender heart, a brave, immediate man who is stronger than her. And it’s worth going to the end of the world for such a man. I left for my then “man of my life” just to America, that means from a comfortable life to another comfortable life. I only lacked professional freedom there, because it is impossible to make your own films like in our country there. But women’s hearts are unpredictable and their bravery is great. I admire, for example, the Czech journalists Lenka Klicperová, Markéta Kutilová and also our Petra Procházková (author of the model), who fearlessly travel to places of war.

To exactly what period is the plot of the film set, what role does the fact play, that everything takes place in a country controlled by the Taliban? How important is the unstable political situation in Afghanistan for your film, which from the trailer seems to be primarily a love story of two young people from different parts of the world?

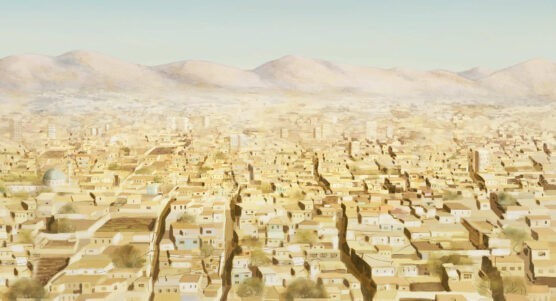

Petra wrote the book around 2004, when there was peace for a while in Afghanistan. Our plot takes place later, around 2011, when the situation started to get tough a bit. Everyone would probably interpret the book differently, but for me it is the main intimate story of family relationships, which is in a way universal. But it is clear that any film set in such a turbulent and dangerous environment as Afghanistan has a political subtext. Life there is infinitely more influenced by external events than anywhere else.

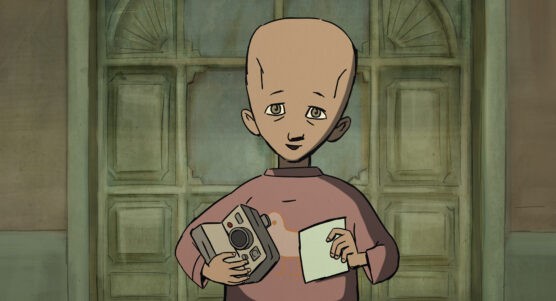

A mysterious boy named Maad enters Herra’s life, whose name also dominates the title of your film My Sunny Maad. How important is this boy coming to a family from some distant mountain for your story?

Maad is assigned to Herra as her child, and after some initial hesitation, Herra finds in him her closest ally. Maad is the mediator. His difference makes him seem a little otherworldly, like Herra he doesn’t really belong anywhere, which is why they are so close.

How hard was it to animate the story of My Sunny Maad, which is set in a real environment and has a real story and characters?

For quite a long time I dealt with the form of the characters and the environment. I started with a strong stylization which is characteristic to me, but then I got scared that the viewer would not believe these characters. So I reworked them into a realistic form, which, however, was very difficult for the animators and it wasn’t my style anymore. The result is somewhere in between.

Was your picture also created at Réunion?

The film was created in a Czech-French-Slovak co-production. The French participated in the music, sound and created half of the animation. The animation studio was at Réunion, an island unknown to me until that, next to Madagascar. At first I was annoyed by this, but in the end it didn’t matter if I commented from home from my computer on the footage from the Alkay studio in Prague’s Nusle district or the footage from Réunion. Thanks to the perfect preparation and the fact that we taught the animators at Réunion together with the animator Michaela Tyllerová for a while, the animation from both studios looks similar, I can’t distinguish it myself anymore.

What was the work like with the actors, who then narrated the individual characters in different language versions? Are you playing the international version of the film at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival?

My Sunny Maad was a tough nut to crack not only in terms of the animation but also in terms of the dialogues. We animated for Czech dialogues, but we also decided to create an international version, where each character speaks their own language. That is, Czech, English and then mainly Dari, which is the most widespread language in Afghanistan. I couldn’t imagine where we would find good Afghan actors or how I would direct them if I didn’t understand their language. However, the Czech version helped us with that, so the actors in the Afghan studio already had a model on how to conceive their scenes in terms of the intonation. To my surprise, the recording in Kabul went very well, I’m excited about the result. They had their director in the studio and I was present online a few times, so I could, for example, coach Nadir on how to pronounce the sentences he had in the Czech text correctly.

And did the actress Zuzana Stivínová speak the voice of the main character Herra in the international and Czech version?

Surprisingly yes. Zuzana Stivínová speaks her internal monologues in Czech, but she also had to record her dialogues in Dari. We thought that for the musically gifted Zuzana, it would be a piece of cake. We didn’t realize how hard it is to learn to repeat a sentence exactly in a language completely incomprehensible to us, and moreover to act these sentences, to act them as an actor, even so that they match the character’s mouth. But Zuzana is a great professional, with the help of our Afghan language consultant, she managed everything very well in the end.

Did you personally go to Afghanistan in connection with the filming?

Unfortunately, I was not in Afghanistan, the producers did not let me go. I had to manage with the videos and documentaries and, of course, references on the Internet. Consultations with Petra Procházková and our Afghan adviser helped me tremendously. To some, this may seem like a very salon approach, but for me, My Sunny Maad is mainly about family relationships, not so much about Afghanistan. There is also a normal life that I wanted to focus on. But I still struggled with their reality. For example, when they said that they would start working later, because there are the most bombings in the morning. That they have a “novelty” there – bombs with a magnet, which a passing assassin, for example a little boy, attaches to a car. I was thinking about how crazy we are here because of Covid that even they have.

You have received a number of prestigious awards for your films – Oscar nominations for the student animated grotesque Řeči, řeči, řeči (Words, words, words), the Berlinale Golden Bear for the short film Repete or the Special Mention from the San Sebastián International Film Festival for Nevěrné hry (Faithless Games). Few not only Czech filmmakers can be proud of so many awards from major film events around the world. What did the awards bring you?

Awards for your work are always tremendously motivating. It’s a personal reward and confirmation that your film works, that you didn’t work hard in vain. The awards help in the next career, you are more visible, you get better support in further work. Of course, it is clear that it is not possible to compare in art, the evaluation is very subjective, it depends on the composition of the jury and personal preferences. I think it would be enough to present a selection, for example the five best films. But I’m not against awards. In addition to prestige and a trophy, you will sometimes receive a financial prize, which in turn will help you in your further work by not having to take orders, it will give you freedom.

You run the Department of Animated Film at Prague’s FAMU, whose students are celebrating many successes around the world. For all of them, we can name the Czech film Dcera (Daughter) of your Russian student, which won the Student Oscar. What do you think is behind the success of animation graduates at FAMU?

I am very happy with the success of our students and graduates. This is due to the long-term direction of our department, which is mainly an elaborate screenplay and also the technical execution, the knowledge of the profession. Perhaps I brought more joy, openness to the department. We give the students as much freedom as possible to express their individuality, at the same time we try to direct them a bit so that their films are coherent, communicate with the viewer, have a readable intention and message, although that can be interpreted differently.

What global trends are you following in this field?

Everything is done, no matter how, in terms of content and form. Nowadays, anidocs, animated films with a documentary element, are very popular. We also pay attention to them in our department, for example the films of Nora Štrbová or Diana Van Cam Nguen are very successful at festivals. I also

notice that many short animated films share a deliberate ambiguity in the message, which reflects the time. But whenever a strong, legible film appears, which, for example, also contains humor, it scores very much in that flood of inner feelings of ruin.

What do you think is a prerequisite for being a good animator? Is this field promising? You yourself graduated from the studio of animated film at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. What would you say to those young people who are considering studying animation?

The animation was, is and will be. Its forms change, it has its high tides and low tides, new techniques appear and then the old ones return… Feature films, series, short films, experiments, story and non- narrative films, music videos, overlaps with game design – animation is still promising. Animation is a field that gives you the infinity of possibilities of self-expression, a drug for life. So consider it well!